Panama Canal (Part II: Gatun)

Thursday, March 8th, 2007

It was now 1pm. Our lock time at Gatun was 4pm. As I’ve mentioned before, Gatun Lake is a critical step when crossing the canal in the Pacific to Caribbean direction; this is because if you are late and miss your lock time, you are charged a bleedin’ fortune ($830, which is more than it costs to make the entire transit) and have to spend the night in the lake on a mooring. Of course, spending the night in the lake is really cool but having to pay so much to do so is ridiculous. The passage is 30 miles from Pedro Miguel to Gatun Locks and we were having a hard time going 8 knots with the weight, wind, and current (even in Gatun lake there was a little current). Not to mention that George was terrified of our outboard and refused to let us go anywhere near full throttle. The possibility of being rescheduled later for the Gatun Locks was out of the question because there was a chemical ship lined up (they transit the locks solo) and they don’t let the small boats go north any later than 6pm or so.

I began to form my argument when/if I had to dispute a late fee. As I saw things, even if we did motor at 8.5 knots, in three hours we would only make it 25.5 miles and we would still miss our scheduled time.

Then George got a call saying that the ship with whom we were to transit the locks was already at Gatun Locks waiting and they were bumping his transit time up to around 3pm. Now there was absolutely no way we could make it. We were released from our nail biting and the threat of having to pay the late fee vanished; George told us with a sigh of relief to just motor at a comfortable pace, which, in his opinion, was about 3 knots—if he could hear the outboard at all, he got antsy. I found his whole motor issue amusing since I can’t imagine the advisors ever get to look at whatever passes for a motor in most sailboats—they are almost always all inboards; they just have to take the word of the captain and what they can’t see they seem to trust. And here was our outboard right out in the open where it could be examined and it was clear that the motor was brand new (shiny).

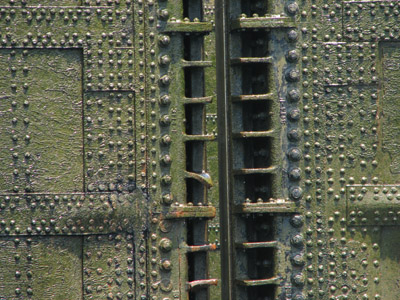

[Totally out-of-order shot of one of the mules. These are used to steady and keep the large ships centered in the locks.]

[Another completely random ‘art’ shot.]

We settled in at a comfortable pace and I went to the galley to make lunch for everyone (with Jan’s help). My exciting chopped salad idea was shot apart when it was clear that with the wind, it would be impossible to deal with anything that must be balanced upon a delicate utensil from plate to mouth so we just made sandwiches and passed around bags of chips (also difficult in the wind but with the benefit of not being saucy). I still find bits of chips jammed in crevices in the cockpit and elsewhere. The boat shimmied around through the Culebra Cut where the wind funneled down in terrific gusts and we were rocked by the wakes of car carriers and other oversized traffic. Finally we made it to the lake proper and decided we needed to up our speed whether George felt it proper or not since we were all getting bored of motoring and we wanted to make the Banana Cut before dark, which is a nifty little detour off the main canal where you passed close among the many lake islands and could often see sloths, birds, etc. At one point, when we were sheltered by a bend in the lake and the wind and waves were not as strong, George looked down at his GPS and was astounded to see that we were going 6.9 knots (we were at 3/4 throttle). After that he stopped giving us a hard time about the outboard.

[Wildlife watching in the Banana Cut.]

We got to the mooring at long last after a full five hours of motoring and it was heavenly to turn the damned thing off. It did fine, by the way, and we calculated that we had burned six gallons of gasoline in the past twelve hours of near-constant use. As soon as we were tied up, I cracked open a bottle of champagne and we stood around the mooring daintily sipping from a variety of frilly glassware, feeling grungy and exhausted.

[Ben gets ready to lasso a mooring.]

The pilot boat came and picked George up. “Will we have you tomorrow?” we asked. But no, it is almost entirely unlikely that you would get the same advisor twice in a row. Besides George lived in Panama City, not Colon, and he had the next day off to boot. Before he left, he gave a brief tutorial to the line handlers about how we needed to be extra careful with the lines when going down the locks and to be sure never to tie them off once the water starts to fall; he seemed genuinely concerned for our little boat. Once the Pilot boat was out of sight and after a perfunctory check for crocodiles, we launched ourselves overboard for a much-needed bath.

[Our mooring buddies.]

Everyone sipped wine and chatted in the cockpit while I commandeered the galley and made dinner: risotto with gorgonzola and pistachios with a salad made from genuine romaine lettuce (the first I’ve had in about a zillion years because Rey Supermercado actually had some in stock that didn’t look entirely pathetic) with a balsamic vinaigrette. Very tasty, if I do say so myself. While dinner was underway, the southbound sailboats transiting the canal showed up and arranged themselves at the mooring buoys. The boat next to us had a couple of kids who spent an inordinate amount of time hopping in circles around the buoy. After dinner we set about transforming Time Machine into a cozy hotel with beds for six people (basically, Joshua and I slept on the trampoline and hoped it wouldn’t rain). Miraculously, almost all our guests brought their own pillows (we only have two on the boat) and so I didn’t need to spring that one on them at the last minute. It did rain that night, but only a few drops.

[Ben applying sunscreen, or else gleefully plotting the takeover of the world.]

On the third morning of our canal transit, we were all up at the crack of dawn when our neighboring boat started their engines in anticipation of an early arrival of their advisor for the day and gagged us all on their diesel fumes. We convinced them to shut it off until you actually see the whites of the pilot boat’s eyes and they felt this was a convincing argument. We were able to drink our coffee in peace. By 7:30, all three Pacific-bound boats were off for their Gatun Lake run. Our pilot boat arrived around 10:30.

[GEORGE!]

As the pilot boat rounded up to the buoy, where they picked up and dropped off advisors, none other than George stepped out of the cabin, a sheepish grin on his face. “GEORGE!” went the general cry. He did not explain how or why but yes, he was back and would be guiding us the rest of the way to the Caribbean. I got the impression by his mild embarrassment and avoidance of questions that he had volunteered out of concern for our boat; unnecessary I thought, but sweet all the same.

[Heading for the Gatun Locks.]

We were underway within thirty minutes and everyone sat around getting ready and passing the sunscreen; we had a vague transit time set for 3pm (good lord) but George felt that a side tie (tied alongside the wall) would be the best transit option and there just happened to be a spot in front of an 800-foot container ship we could snag; this would bump our transit time up by several hours as well. Canal transit clerks automatically mark the “NO” option for side tying all sailing vessels after once a sailboat rolled in the turbulence and got rigging tangled against the wall. We’re so wide and we don’t roll so this would not be a concern (we tried to explain this initially to the admeasure—the person who inspects and measures each boat that wants to transit the canal) but he wouldn’t even look up from his paperwork to look at our boat. George produced a side-tie waiver for us to sign and we were moved up in schedule.

I was back on the stern with my pet outboard and we were advised to slip in front of the gigantic ship, tie alongside the wall while the first lock filled back up with water (this creates significant current sometimes), then we would be in place ahead of the ship and wouldn’t have to dodge propwash from the tugs to enter the lock. “Basically,” Joshua shouted back to me, “this is going to be hairy.”

[The ship being pushed into place.]

I untied the outboard to have steerage and we motored up to the wall outside the lock to tie up. I kept the motor in reverse and pointed the propeller at the wall to keep our ass in line when the current started. We looked back at the water churned up by the tugs and what looked like a mere 50 feet of clearance between them and the canal wall that we would have had to get through had we not gone in ahead while the lock filled; THAT, would have been hairy.

[Typically, there was a lot of standing around with hands on hips going on aboard the Time Machine once the excitement waned.]

Once the lock was ready for us and the doors opened, we untied and motored to the very front of the lock. Joshua steered until we got almost into position and then I steered us back and forth as if we were parallel parking. The lines were made taught on the port side and that was that. We stood around in the blazing sun waiting as the mules pulled the container ship into place. In a 1000-foot lock, an 800-foot ship feels really close and really big. Once in place we were almost looking straight up at their bow.

[Honkin’ big ship.]

The side tie situation went incredibly smooth for us. Basically, only two line handlers were needed to let out line as we sank down and the rest of the bunch just stood around looking at the wall, which was covered in black slime and artifacts of ancient canal accidents. I sat on the stern taking photos: port side, starboard side, behind at the ginormous ship, off. Repeat thirty seconds later. Consequently we have about a million almost identical photos of pretty boring stuff. Once we were down and the doors open, the lines were thrown off and I steered us out into the middle of the lock where Joshua could take over steering until we got up into position for the next lock.

[Gary on wall detail.]

[The typical standing around wall scene.]

We repeated this three times without incident and at last the doors opened to the Caribbean where we motored out of the lock for the last time, waving goodbye at the Gatun line guys and the crew clustered at the bow of the ship behind us.

[Posers.]